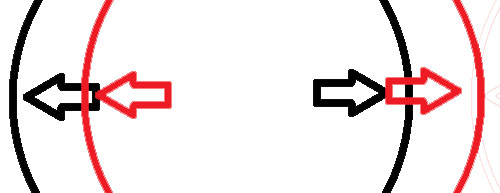

“Political discourse is dead in America. We can’t debate each other anymore. Open dialogue between opposing viewpoints has been cut off completely, and instead we all now seek out whatever echo chamber we find the least [logically] challenging, wall ourselves off from the rest of the world, and listen to the soothing voices tell us how right we are.”

Those are the words of a thinking liberal, Caitlin Johnstone. The concept of an echo chamber has been around for a long time. We see it politically on a regular basis. But I’m afraid that we might also be suffering from the problem in some theological circles. We like to sit in church and hear the doctrines we accept repeated over and over and over. Seldom are they updated and even more infrequently are challenging questions entertained with honesty.

This concept was first clarified to me in seminary (TEDS) with Alice Ott saying in our missions history class that, if I recall accurately, “We’re in seminary. We can read things we disagree with.” Her goal was reinforcing our faith with a stronger application of it to the world around us.

Now, I’m not supporting the old ecumenical idea of dialogue with everyone and that all ideas are equal. Those days are past. What I would rather encourage, instead of simple dialogue, is open debate. Let’s disagree and do so with fervor. But let’s not treat alternatives, especially within the confines of the committed evangelical community, as an anathema. I seems valuable that we have our intramural discussions first, and the we can go to the world with some additional sense of unity.

Some of this happens in systematic theology. Recall the systematic of Chafer. It’s straightforward exegetical approach. That has its place. But, unlike A H Strong he does not give it application so that it might challenge Ritschl or Darwin. (Ok, Strong has a problem with inclusivism. But that’s another discussion.) The point here is that Strong gave his systematic a broader application, an apologetic place, in the life of the church. Is that of value to us? The subject might be worth debating.

Let’s talk about eschatology for a minute. The fundamental fellowships cling to dispensationalism as though it’s the only principle taught in the Bible. But in the 19th century most of the evangelicals were either postmillennial or amillennial. Premillennialism was on the rise, along with its child dispensationalism. But it wasn’t there yet. Two hundred years ago today’s assumptions were rejected by most — and that would have been among the most doctrinally precise evangelicals.

There’s one hard question that both the amillennial and premillennial community should grapple with: Why are the covenants fungible but the plan for history not, or conversely why is the plan for history fungible but the covenants are not? Did God really institute a change of plan? Was there really a change of relationship? Were not all of His promises to be taken with equal seriousness? I’ve not read a book yet (though there may be one, I’ve not seen it) where a theologian would acknowledge the legitimacy of the questions posed by the other side of the issue and so grapple with them.

Now to something really offensive: The question of creation. No, I’m not going to suggest that we accept theistic evolution. But there are lots of other questions. For instance, we know that New Testament doctrines are built around, not 6,000 years, but six days. What if the earth is more than 6,000 years old, but still a special creation? What if the 6,000 year principle, per Usher, was really a contrivance to try to predict the return of Christ somewhere around the year 2,000? Can we face the whole question while remaining orthodox? It seems we can but few will.

We sit in our churches and query nothing. We’re told not to question orthodoxy. And when we fail to investigate we become that empty echo chamber. We don’t learn the history behind our doctrines. We end up with a surface perspective on the world and God’s work.